Architecture can be a harsh mistress.

About 10 years ago I quit the world of accounting to pursue architecture. I don't think I can quite pinpoint the reason why - I liked making things, and thought I might enjoy it more than the safer path I was pursuing. Looking back, it seems like an odd choice given that 1. I was exceptionally good at accounting and 2. I had already invested a huge portion of my life getting the degree. And there are days - like this previous Friday, as I slunk back to my car defeated once again by Architecture - where I wonder how much easier my life would have been had I not left.

I came into this profession with only a bit of woodworking as the entire arc of my artistic experience. When it came time to submit a portfolio, I had to rely on the small bit of mediocre work I had gathered to apply to grad school. Once there, I found that I couldn't rely on my intellect alone to get by; architecture demanded an artistry that was foreign to my traditional sensibilities. I struggled early on to make the leap from the pragmatism of building to the conceptual practice of architecture, and this often manifest itself in harsh reviews and unfavorable work.

Looking back I realize that my two best assets were not innate talent nor intellectual perception; instead they were my work ethic and my resilience. In spite of my early failures in architecture, I managed to keep a surprisingly optimistic attitude, and this - combined with a personal ethic that would not permit me to be outworked - kept me in the game. I know it's this combination of resilience and hard work that has gotten me to where I am today.

I hate failure. Failing never gets easier. I think the term "fail fast, fail forward," is just some new age bullshit to help assuage one's ego after a tough event. Even after all these years, every time I fail something it still hits me like a ton of bricks, and leaves an imprint on my memory that lasts for years on end.

This year I was a finalist for the Rapson fellowship for the third time and, for the third time, the prize was awarded to someone else. It's easy to say that this is just "the nature of competitions," and "it's great that I've made the finals so many times," but if I'm being honest, this one hurt in a way that I hadn't felt in a long, long time - and it's a hurt that still persists as I write this. It's a hurt that keeps me up at night as I try to fall asleep, and it's a hurt that wakes me up in the morning. And its a hurt that I haven't been able to ameliorate through exercise or distraction or even other success. As my boss wisely told me "it's a hurt that's going to just take time."

As I have dealt this week with the aftermath and recovery, I've continued to think about my other failures in architecture, and how those have shaped me and brought me to where I'm at. To give you an idea of what I'm talking about, here's a very, very abbreviated list of my failures in architecture:

2007: Receive the an exceptionally harsh review of studio work. This is only the first of many.

2008: Receive a C+ in design studio; a mark I hadn't seen since 5th grade.

2009: Apply for scholarship at school for design; don't get shortlisted.

2010: Apply to a myriad of different architecture firms; get no calls back. Take job at Target corporate headquarters as a contractor doing mostly busy work, mostly hating each and every day of it.

2011: Interview twice for my dream job; get rejected.

2011: Do my first St. Paul Prize; don't make the shortlist.

2011: Do my first, second and third international competition; don't get shortlisted or awarded.

2012: Do my second St.Paul Prize; don't make the short list.

2012: Do my fourth, fifth and sixth international competitions; don't get shortlisted or awarded.

2013: Do my third St. Paul Prize; don't make the shortlist.

2013: Do my upteenth international competition; don't get awarded.

2014: Do my first Rapson; get shortlisted but don't win the fellowship.

2015: Do my second Rapson; don't get shortlisted.

2016: Do my third Rapson; get shortlisted but don't win the fellowship.

2017: Do my fourth Rapson; get shortlisted but don't win the fellowship.

Every single one of those hurt. I can pinpoint where I was and what I was doing when I experienced each one of those failures, and the disappointment I experienced with each is every bit as tangible now as it was then.

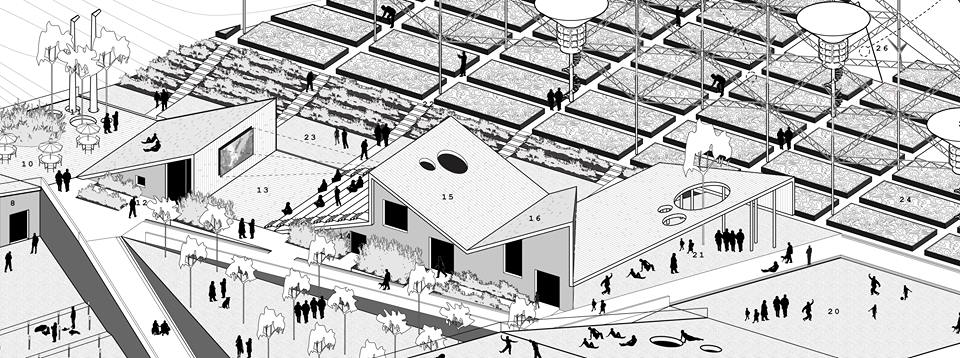

SPP 2014 - one of many "failures."

Like I said, I hate failure.

But it's these failures that have also brought about the successes I've enjoyed in my life. I've put skin in the game over and over and over, and as a result, I've won some competitions, been published, received some awards and gotten to work on some incredible projects as a result of my persistence. I don't say these things to brag, but rather to make this point - failure hurts, but it only hurts because it demands a vulnerability that also engenders success.

This most recent failure hurt worse than most, because I think I made myself more vulnerable than ever before by investing more of myself than I ever had. The first year I made the Rapson finals I didn't know any better and I was just happy to be there; the second year I made the finals I honestly didn't love my project much, and thus was somewhat surprised to be selected; this year I loved my project, I loved my concept and I poured the entirety of myself into preparation for two weeks before my speech - and came up short. I wanted to win this year, more than ever - I was done being satisfied by merely participating, and despite that, I still failed.

A rendering from this year's failed venture.

Such is life.

For days after, I was convinced I'd never do the Rapson again. I'm 31, so technically I have 9 years left to try again, but this year took such a physical and emotional toll on me I couldn't even imagine picking up a pen to try for another time.

But as I sit here and look back at my many failures in this profession, I realize that the successes I've had necessarily require the risk of failure; that without making myself vulnerable to the pain and hurt failure can cause, I'd probably still be living my life in the relatively safe world of accounting.

John A Shedd said that "A ship in harbor is safe, but that's not what ships are built for." This profession demands a vulnerability that opens one's ego to criticism and failure unlike few others - like I said, Architecture is a harsh mistress.

But in retrospect, I realize that those failures are an absolute necessity to get to the successes. And that it wasn't my talent nor intellect that has brought whatever modicum of success I've enjoyed; it's been my resilience and persistence.

Failure sucks. It hurts in deep, persistent ways.

But at the end of the day I figure I have two choices - I can either quit and recuse myself from the potential of that pain ever again, or I can use it as fuel.

I think I'll choose the latter.